New Grad Techie's Guide to US Retirement Accounts

This is a quick guide to how retirement accounts work in the US from the perspective of a new grad in tech. As a quick disclaimer, I am not an accountant, financial advisor, nor a lawyer. I’ve just spent a bunch of time researching this as someone who didn’t know anything while moving from Canada. You should consult financial experts (aka not me) when making financial decisions.

Last updated: January 1, 2020 (using 2020 contribution limits)

Investment account types

(Backdoor) Roth IRA 🚪

The Roth IRA lets you deposit up to $6k in cash into the account every year. In 5 years, you’re able to withdraw the original $6k tax free [1]. All interest on the invested amount can also be withdrawn tax free when you reach 59.5 years old.

Your income is likely too high to make a full direct contribution to the Roth IRA (over $124k a year, including stock and bonuses), and also probably too high to deduct income through a Traditional IRA. This means you’d probably want to contribute through a Backdoor Roth IRA.

The steps to a Backdoor Roth IRA are:

- Open a Traditional IRA account and a Roth IRA account

- Contribute $6k into the Traditional IRA without any withholdings

- Convert the $6k into a Roth IRA account

- File a Form 8606 when you report taxes to declare the contribution as non-deductible

This is a great place to put a portion of your starting bonus! You need to make your contribution and finish your conversion by the end of the year. [2]

You likely want to open your Roth IRA ASAP even if you mostly focus on funding your 401(k) because of withdrawal rules.

Pre-tax or Roth 401(k)

This retirement account is funded by taking a percentage of your paycheque. You are able to contribute up to $19.5k in 2020 (it usually goes up a bit each year). Two of the ways to contribute are to pre-tax and Roth accounts. The limit is for the total contributions to these two accounts combined.

- Pre-tax 401(k): This is like putting aside some of your income to earn it later. You save income tax on it now (as if you didn’t earn the income), but then you pay income tax on both your contribution and interest when you withdraw from the account. This is ideal if you think you’ll be paying less taxes when you retire than right now, which is likely as you probably will withdraw less in your retirement than you’re earning right now.

- Roth 401(k): This is like the Roth IRA, where you’re putting income that’s already taxed into your 401(k). You don’t pay income tax on the contribution nor the interest when you withdraw. This is ideal if you predict you’ll pay MORE taxes when you retire than now. This might be the case if you’re moving to a higher cost of living or a higher income tax area (ex. working in a state with no income tax and low cost of living and then retiring in SF or NYC).

You likely want to contribute at least as much as what your employer matches.

💸🚪 Mega Backdoor Roth 🚪💸

The total amount you are able to contribute to a 401(k) in 2020 is $57k. This is the sum of your pre-tax and Roth 401(k) contributions, your employer’s match, and your after-tax contributions.

If your employer allows you to make after-tax contributions, then you could contribute extra to fill the rest of the $57k that’s left over after your normal 401(k) contributions and the match. Then, you’re able to move your money (i.e. “rollover”) from your after-tax 401(k) to a Roth 401(k) or your Roth IRA using a process called the Mega Backdoor.

- If your 401(k) provider allows you to automatically rollover your after-tax 401(k) to a Roth 401(k) or a Roth IRA, you should set this up first

- Set a percentage of your income to go towards your after-tax 401(k)

- If you don’t have automatic rollover configured, then you’d want to call your 401(k) provider to rollover your after-tax contributions to a Roth account immediately after getting paid each paycheque to avoid getting taxed on interest in your after-tax account

Other tax advantaged accounts

- Health Savings Account (HSA): If you have a High Deductible Health Plan, you can put pre-tax funds into the account to use for healthcare expenses

- Flexible Spending Account (FSA): Your employer may provide a FSA where you can contribute pre-tax funds into an FSA for healthcare expenses

Restricted Stock Units (RSU) 📈

This is not a retirement account, and is not tax advantaged.

When you receive RSUs, the amount at which you vest is considered income and you’ll pay income taxes on it on the year you vest. If the price of the stock goes up, then you’ll pay capital gains tax when you sell.

For example, let’s say you vest $10k worth of stocks. If your income tax is at 30%, then you’ll pay $3k in income tax for that vest. Your employer might sell some of your stocks on vest to pay for a portion of that income tax, and the rest you’ll end up owing IRS when you file your taxes.

Let’s say your $10k of stocks become $12k, and you sell.

- If you sell your stocks within a year of your vest date, then you’ll pay income tax on the gains. So in this case, you’d pay additional income tax on just the $2k.

- If you sell your stocks after a year of your vest date, you’ll pay long-term capital gains tax, which is likely lower than your income tax, most likely 0% or 15%.

If you sell your stocks immediately after they vest, then you won’t be paying (or you’ll be paying a minimal amount) of capital gains taxes, since there would not be (much) gains on the stock from vest to sell time. It’s helpful to think of vests as your employer immediately paying you the vesting amount in cash and then you spending all of that cash on purchasing your company’s stocks.

Non tax advantaged accounts

You can also invest directly through a brokerage like Vanguard or Robinhood. This is like RSUs, except you’re using your cash (i.e. already taxed money) to invest instead of the stocks vesting. You’ll be paying capital gains when you sell. You can also use tax-loss harvesting to decrease the amount you pay in capital gains.

High Interest Savings Account (HISA)

This is not actually an investment account, but you should have 3-6 months worth of your expenses in cash in case of emergencies. You can put it inside a High Interest Savings Account to get at least some interest on the savings.

Index funds

In the 401(k), IRA, or your non-tax advantaged accounts, there’s a variety of ways you can invest your money. I don’t want to give investment advice, but a common one nowadays is using index funds, which directly track the (stock/bond) market with minimal fees. You can look at the Bogleheads wiki to get some examples of how people invest in this way.

Lots of tech companies, by default, will invest your 401(k) contributions to Target Date Funds which starts off stock heavy with lots of potential growth and a lot of risk, then slowly switch to safer investments like bonds over time as you get closer to retirement age. This could be a good option if you don’t want to think about how to invest your money, though you should talk to a financial advisor for your specific needs.

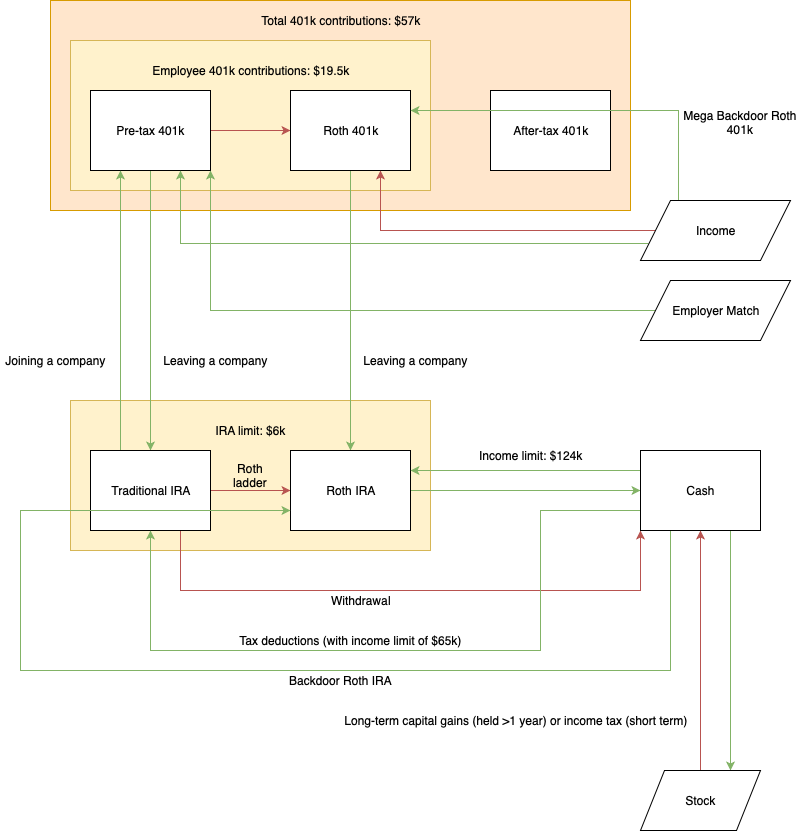

Moving money between accounts

You’re able to move funds from your 401(k) to your IRA (likely when you leave a company). You can also rollover 401(k) funds to other 401(k) funds when you join a new company.

You can rollover your Roth 401(k) to your Roth IRA, which is helpful if you want to withdraw your funds earlier before retirement. In this case, there’s rules that determine when you can withdraw your Roth 401(k) funds after rolling over to your Roth IRA. In general, if you’re planning to do this rollover, you should open a Roth IRA early to meet the 5 year rule.

Moving to an IRA can be helpful since you may have access to more choices of investments than what your employer offers. But there’s pros and cons of rolling over from 401(k) to IRA, and there’s other factors to consider like lawsuit protection in 401(k)s. It’s possible that your 401(k) could have better options than you could get individually in an IRA as well.

Here’s a somewhat convoluted diagram to show you ways in which you can transfer funds between accounts.

If you’re planning to FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early), then you can use a Roth conversion ladder to slowly funnel your pre-tax retirement funds to Roth accounts while minimizing tax paid.

Footnotes

- [1] If you make a direct contribution to a Roth IRA, you can withdraw the original contribution (principle) at any time. The 5 year period is assuming you do a Backdoor Roth IRA.

- [2] This is because you’re doing the Backdoor. Otherwise you’d have until April for direct contributions.